A topic today in jazz education is creating a rift between students and their teachers—PERSONAL STYLE. I recently attended the Jazz Education Network conference and the Navy International Saxophone Symposium, and neither conference had sessions that addressed personal style. The sessions were mostly “how-to” lessons for sound, phrasing, how to navigate chord changes, etc. I have been curious about why so little of what we educators offer has to do with creativity.

Many of our students are drawn to performing and learning jazz because they want to have a personal style. They want to have the freedom to make musical choices without being told what to do. High school saxophone players who attended my Symposium session said they like jazz because they want to play whatever they want. I will later detail why this assertion is problematic.

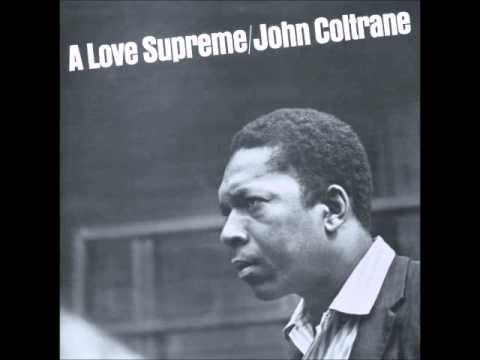

The personal style of great artists is what excites us. It is absolutely astonishing that we can hear a fragment of a phrase by Billie Holiday, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, and others and know exactly who the artist is. Drop the needle at virtually any point in this album and most seasoned jazz listeners would know exactly who the artists are:

WHY is personal style not more often addressed?

I have been pondering this for several weeks and I think that these are some reasons why so few educators avoid the topic:

So many of our students are beginners or at only an intermediate skill level. It takes a more advanced level of musicianship to be able to address a personal sound.

There is no expectation that educators teach personal style in jazz education. The expectation is rather that students learn tangible, basic skill building.

Maybe teaching personal style is difficult?

MISUNDERSTANDINGS about Personal Style

As I previously mentioned above, students sometimes errantly assert that jazz is about freedom and doing whatever we want to do. Here are reasons why this is problematic:

It would be more accurate to say that jazz affords musicians to have freedom within a structure. The structure could be a tune, a chord progression, a rhythm, a rhythmic pattern, or something else that is established. A few years ago, I performed a run of shows with the Dutch drummer Han Bennink, who is generally known as a free jazz drummer. He gave a master class at one of the music schools in Boston and was absolutely livid that students were getting lost in a blues form!

We are tied to the roles of our instruments within the context of an ensemble. For example, the rhythm section are often support players—supporting a vocalist or an instrumental soloist. I once saw Dave Holland in a master class, and he made a huge point of saying that Miles Davis would remind him that he is a bass player and that bass players play LOW notes and that was his role in the band. Similarly, I, as a saxophone player, generally would not comp behind a soloist because sax players generally do not comp as pianists do.

We cannot ignore the tradition of jazz, which includes idiomatic aspects of the art form—swing, phrasing, harmony, etc. Ignoring the tradition of the music results in an inauthenticity that is generally considered unacceptable.

HOW TO DEVELOP PERSONAL STYLE

When I studied at the conservatory, every semester we had a “Development of Personal Style” course that was taught by a revolving cast of professors. Regardless of the professor, the expectation was a deep, deep study of existing artists to best hear, understand, and internalize their music and ideas. Personal style is actually rooted in studying existing music and musical traditions rather than sitting alone introspecting.

A really great example of an artist working on personal style is the first recording of John Coltrane:

This is John Coltrane playing the Charlie Parker tune KoKo in the style of Charlie Parker. This is John Coltrane in 1946, nearly two decades before his recording of A Love Supreme, which was recorded in 1964. This is an example of an iconic jazz figure who deeply studied the tradition of bebop — Coltrane clearly was deep into the study of Charlie Parker.

Truthfully, there is no easy path to developing a personal style. When I was 21 years old I took the Lydian Chromatic course with George Russell. George liked one of the compositions that I wrote for the class, so I stayed after class one day to talk to him. I knew that George was friends with Ornette Coleman and I was infatuated with Ornette, so I asked George to introduce me to him. I hoped to learn as much as I could about Ornette. George told me very firmly that meeting Ornette would be a waste of time and a more meaningful use of time would be to transcribe his huge body of recorded music. George was so right — there is NO easy path to musical enlightenment.

Here is my best advice for young musicians working on finding their personal style:

Play your instrument well. Virtuosity and the ability to play the instrument well is non-negotiable. Learn from the best teachers, practice their assignments, and surround yourself with the best players you know who play your instrument. Practice with peers who are accomplished, even if they play different styles of music than you play.

Listen to a lot of music. Know albums and not just playlists. Listen daily. Try to listen for a minimum of 20 minutes per day. Try to listen with music in the foreground and not the background.

Listen to a wide range of music. Don’t just listen to what you play. Don’t just listen to bebop, or jazz, or only people playing your instrument. If you are a trumpet player, listen to piano trio music. If you are a pianist, listen to Billie Holiday. Listen to drum and bass music, reggae, Latin, and every style of music from the African diaspora.

Internalize music. Transcribe music. Sing along with recordings. Memorize melodies, be able to play ii-V’s, practice ear training, play pieces in multiple keys. Don’t just learn patterns with the fingers.

Write music and interpret other music. Create music and write it down. Have other people play your compositions. Use DAW software to write, use pen and paper, write at the piano, and explore every option. Write arrangements of other peoples’ compositions. Find alternative harmonies for pieces and explore pieces in new meters and rhythmic subdivisions.

As always, I am curious about what input I have from students and colleagues who see this. I am interested in an honest dialog that can bring educators and students together.

Meeting Ornette was a waste of time? Come on now!